A recent study conducted by Friends of the Earth and published online by Elsevier in the journal Environmental Research explored whether an organic diet would reduce levels of urinary pesticides.

Previous research has done similar studies but they mostly focused on organophosphate pesticides. This study looked at pyrethroids and neonicotinoids, two compounds that are used increasingly in crop production around the world. Neonicotinoids have become one of the most widely used class of insecticides and they account for some 20% of the current global insecticide market.

The fascinating thing is that the study found that switching to an organic diet significantly reduced levels of pesticides in all participants after less than one week.

“On average, the pesticide and pesticide metabolite levels detected dropped by 60.5% after just six days of eating an all-organic diet,” the press release stated.

But here’s the rub.

The study was conducted on only four families represented by seven adults (ages 36-52) and nine children (ages 4-15). They were from Oakland, Minneapolis, Baltimore and Atlanta. Nine were Caucasian, four were Hispanic/Latino and three were African American.

The study was short – just 12 days – but very controlled. For the first five days, participants all ate their conventional diets. During days six through 11, they were all provided with certified organic food to eat whether at home, school or work. Dinners were prepared with all organic ingredients by a licensed chef or caterer and delivered to the participants by the research assistants. The trial ended on day 12 after the final urine collection (158 urine samples in total).

According to the report, there was a 61% drop in chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate pesticide considered moderately hazardous to humans by the World Health Organization, a 95% drop in malathion, an organophosphate insecticide, and an 83% drop in clothianidin, a neonicotinoid pesticide believed to be a main driver of huge pollinator losses. The study also showed a 37% drop in pyrethroids, and a 37% drop in the world’s oldest herbicide 2,4-D. In 2016, the Pest Management Regulatory Agency, a division of Health Canada, concluded in its special review that 2,4-D is not a carcinogen.

What made the study interesting was that the levels by which pesticides and herbicides dropped following a switch to an organic diet occurred in less than one week. The study built on previous research by examining dietary exposure to pesticides that have not been studied in similar intervention research in the past. This study recorded reductions of metabolites in urine samples in 13 pesticides and compounds.

And that begs the question that if these insecticides disappeared so quickly in such a significant amount, how non-persistent are they? And how are scientists rating their danger level?

While claims are made in the report of the many and varied health hazards from exposure to pesticides, it would be helpful to have better clarification on the level of exposure relative to duration and circumstances. This would be valuable for all consumers.

However, the report did acknowledge that gaps exist regarding specific health effects to chronic low-level exposure. The researchers also referred to a study done in 2018 that looked at the consumption habits of 70,000 adults and found that a higher frequency of consuming organic food was protective against several cancers.

Quick to shed

“This important study shows how quickly we can rid our bodies of toxic pesticides by choosing organic,” said Sharyle Patton, director of the Commonweal Biomonitoring Resources Center and co-author of the study.

Ideally, we all want food that is pesticide/herbicide free. But it can come with another cost not always considered.

Studies have shown that organic yields are generally lower than yields from conventional farming since fertilizers are not used. To produce all our food requirements organically would require farming more land and this could impact climate change.

In an international study conducted by Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, researchers developed a new method for assessing the climate impact from land use. After comparing organic and conventional food production, results showed that organically grown food can result in greater emissions because of the greater land use demand, a fact not always taken into account in comparisons between the production of organic and conventionally produced food.

“The greater land-use in organic farming leads indirectly to higher carbon dioxide emissions, thanks to deforestation,” said Stefan Wirsenius, associate professor in the Department of Space, Earth and the Environment, Chalmers. “The world’s food production is governed by international trade, so how we farm in Sweden influences deforestation in the tropics. If we use more land for the same amount of food, we contribute indirectly to bigger deforestation elsewhere in the world.”

The FOE study is a fascinating look at pesticide levels in humans and, in the bigger picture, it clearly deserves more research to understand not just dietary exposure but climate implications.

Margaret Evans is a freelance writer based in Chilliwack specializing in agricultural science.

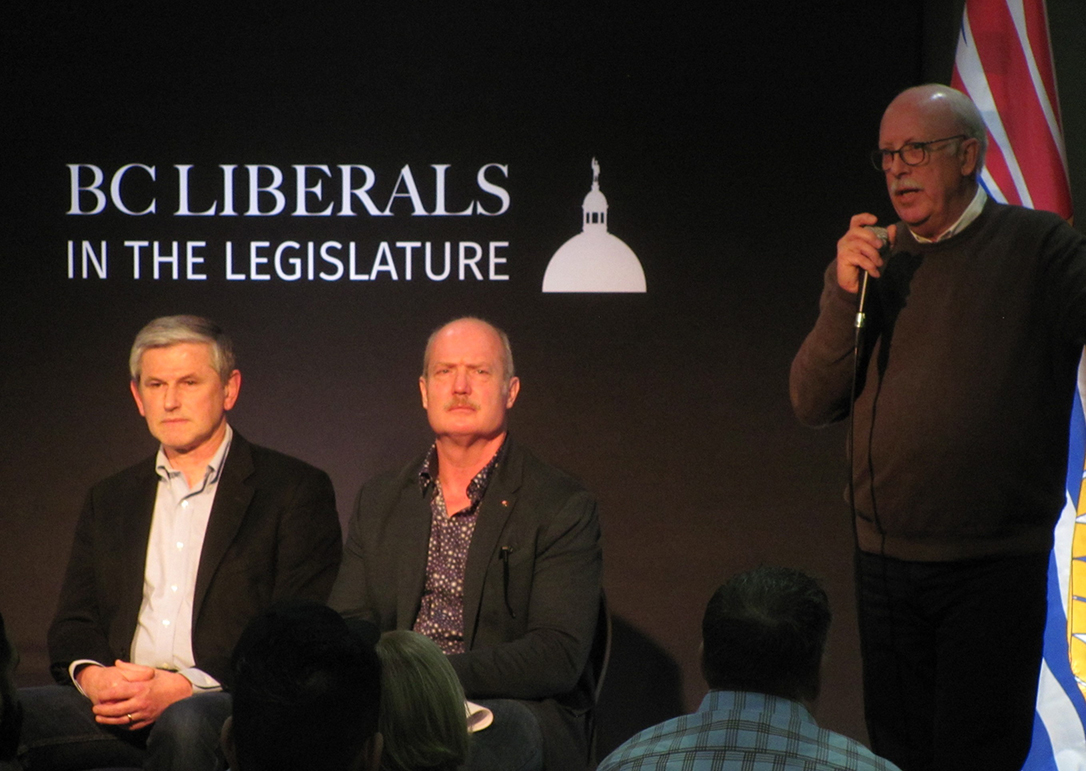

NDP declare “full-on war on farmers”

NDP declare “full-on war on farmers”